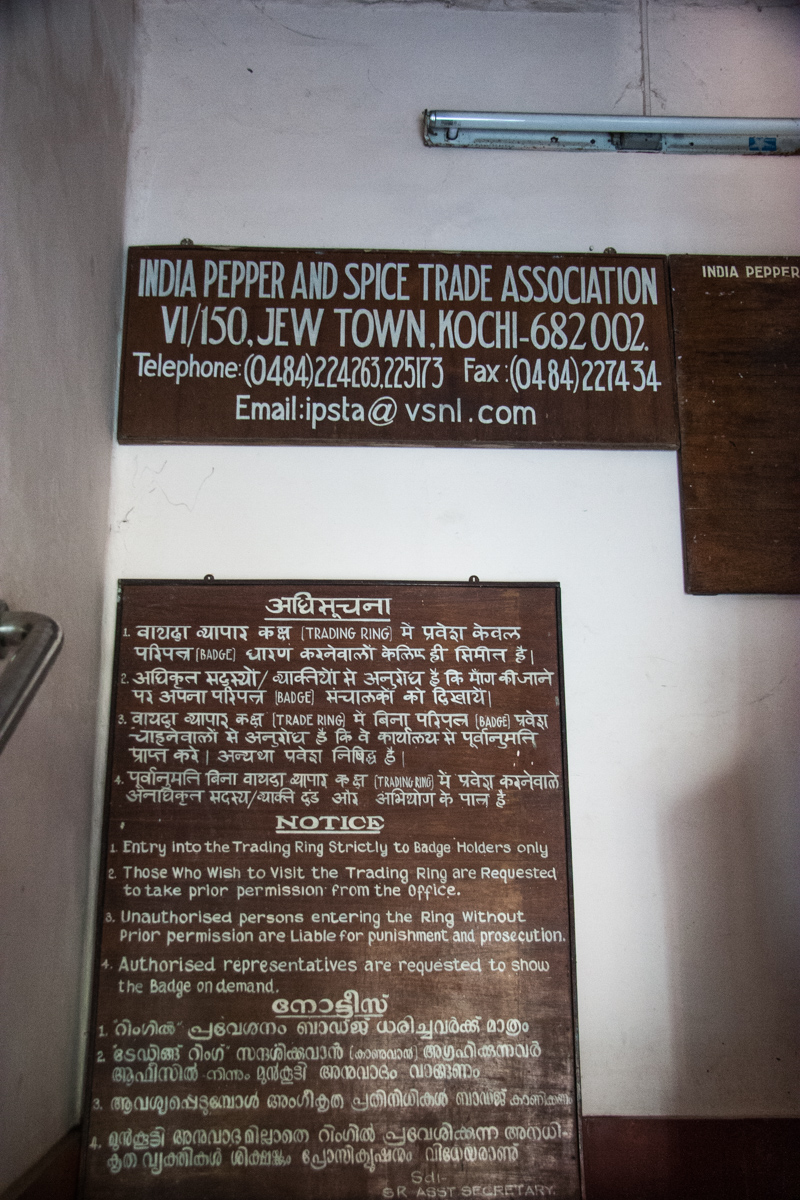

While we were staying in Fort Cochin, we spent one of our afternoons exploring Mattancherry, the adjacent district to the east that is also part of the larger urban area known collectively as Kochi. This was the original trading hub of the region and is still at the heart of the spice trade. There are warehouses and shops selling spices and tea all through this quarter. It is also home to the International Pepper Exchange, which controls the lion’s share of the black pepper business worldwide.

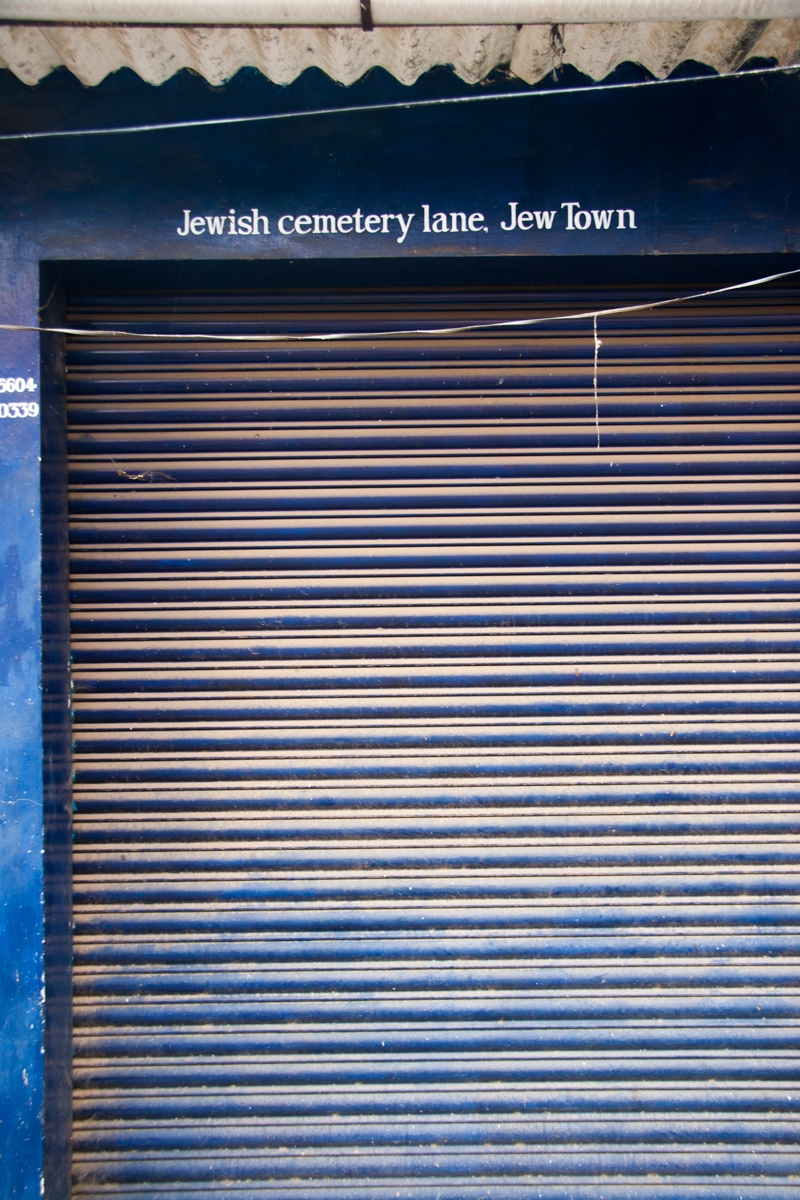

In the center of Mattancherry is the Jewish district, “Jew Town,” which is home to a Jewish cemetery and the oldest working synagogue in India – which also happens to be the oldest continually functioning one in the entire British Commonwealth. This part of town is a popular tourist area, and as a result you see signs that read “Jew Town,” all over the place. This was jarring to us every time we saw it, but I got the sense that it’s matter-of-factness and not bigotry that lies behind this moniker.

Jews have been well integrated into this society for a long time. A really long time. Some believe that the earliest settlement of Jews in the area dates to King Solomon’s time (about 950 B.C.) The first sizable Jewish settlement was in the ancient port of Craganore, near Cochin. It was populated by a wave of immigrants who came to the area after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 A.D, which is about the time that St. Thomas is said to have brought early Christians to India. Historical evidence shows that the early Jewish settlers enjoyed good relations with the Indian rulers of the region. A decree from a Hindu raja in 379 A.D. granted their leader the status of a prince, and established key privileges for the community: the right to live freely, build synagogues, and own property. In essence, the Jews were granted their own princely state. These rights were conferred in perpetuity, and engraved on a set of three copper plates that still survive.

Over time, the community migrated south to Cochin, and a newer wave of Jewish immigrants, the Paradesi or “White Jews,” began arriving from Europe after 1500. Many were fleeing the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal. The existing community came to be known as “Black Jews” or “Malabar Jews,” and tensions between the two groups emerged quickly. They did not integrate well and the communities remained quite separate.

All of the Cochin Jews got a bad time from the Portuguese while they controlled the area, but things improved for them when the more tolerant Dutch assumed control in 1660. Since that time, the community has all but died out in Cochin. By the 1940s, their total number wad about 2,500. Most have emigrated since then, with a many going to Israel shortly after it became a nation 1n 1948. Today, the community remaining in Cochin numbers about 50. It includes just one woman of childbearing age, and it does not appear that she intends to have children.

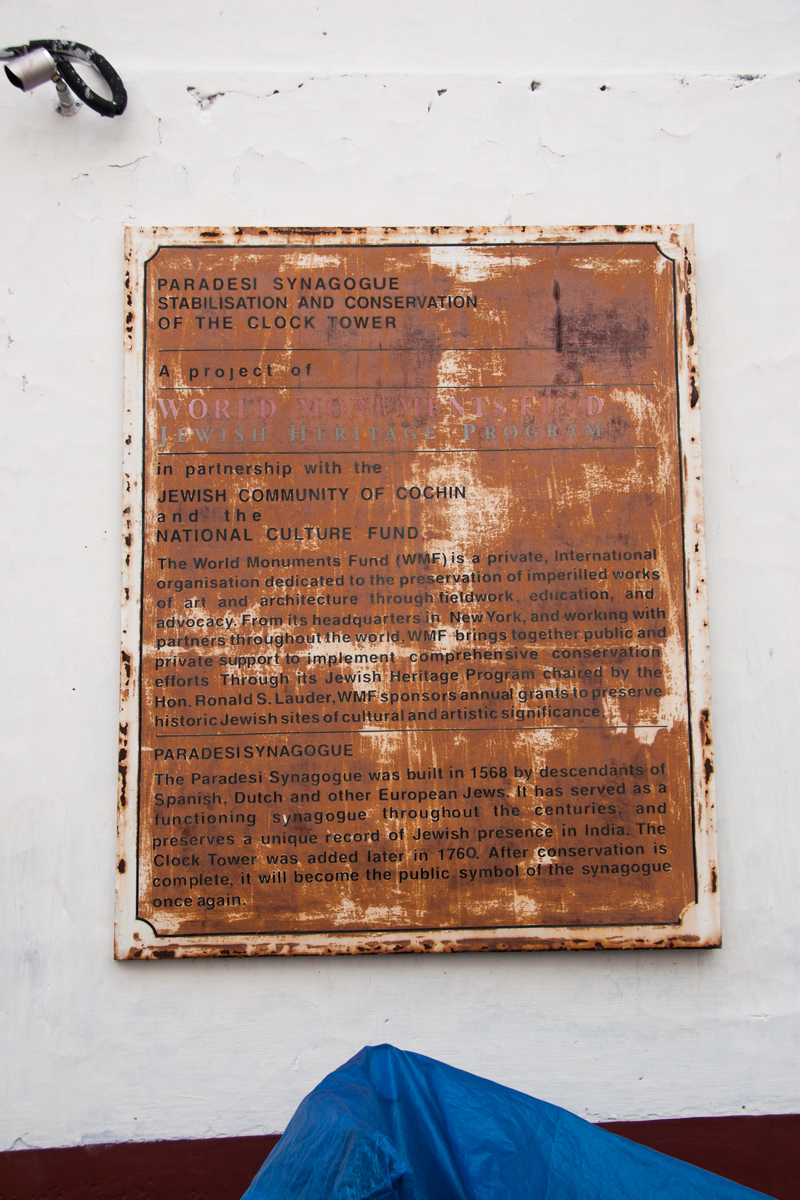

Though at one time there were eight synagogues in the Cochin area, the Paradesi Synagogue is the only one that remains active. It was built in 1568, after the destruction of the original synagogue by the Portuguese in the 15th century. The building was damaged in 1662, and was rebuilt in the mid-18th century.

Visitors are required to leave cameras and shoes at the door. There is a small museum area inside the building that has a series of posters explaining the history of the Jews in Cochin. The interior of the synagogue is not very large, but it is bright and airy with a high ceiling and white walls. The floor is covered with hand painted blue and white Chinese tiles, each one different, that were added in the 18th century. The most striking feature is the large collection of colorful glass lamps and chandeliers suspended from the ceiling.

Our visit did not take too long, and we were soon back outside, running the gauntlet of pushy shopkeepers that lined Synagogue Lane. We managed to get out of their range, and walked for a bit through the quieter parts of town to find the Jewish cemetery. Unfortunately, this was closed to visitors, and looked pretty overgrown from what we could see through the gates. We spent some more time walking through this neighborhood and photographing, then worked our way back to the more touristy district. By this time, it was getting to be late afternoon, and we could see heavy black clouds to the west that told us that rain was coming, and soon.

As soon as this realization struck us, a few fat drops began falling. We quickly hailed a tuk tuk to get us back to Fort Cochin, figuring they were going to get scarce when the rain really started coming down. Once back in the downtown area, we ducked into the restaurant of one of the swanky hotels. We were safely inside, but had a view out to the courtyard and swimming pool. We ordered snacks and coffee, and then watched the show as dusk fell and the downpour began in earnest, punctuated with dazzling lightning flashes and intense thunder. There is nothing quite like a thunderstorm in the tropics.

After the rain subsided a bit, we caught another tuk tuk back to Beena’s in time for dinner and a fun evening of conversation with our fellow guests at the homestay.